Cochise County Cowboys were publicized around the country during the 1880s. The Wild West attracted adventurers, pioneers, miners, and cattle ranching. All became attracted to this frontier for opportunities. Mexicans had been here for generations, many having been raised in ranching in the tradition of the vaqueros.

What is it about Cochise County “Cow-boys” that attracted attention? Getting this infamous reputation through newspaper stories. Plus even the U.S. President’s attention in Washington D.C.! We’ll find out. Let’s first briefly review Tombstone Arizona’s beginnings that gave rise to these Cow-boys of Cochise County.

When Was Tombstone Founded?

In the 1860s Frederick Brunckow mined just Southwest of today’s city of Tombstone. He was the first non-native person to establish a settlement in the area. Read the Brunckow Mine History.

Who Founded Tombstone Arizona?

Ed Schieffelin, was a mining man interested in Camp Huachuca surroundings. He asked to go with a military force on patrol. He liked the troop’s safeguards. But eventually was frustrated by the restraint for going his own way.2

How Tombstone AZ Got Its Name

Schieffelin decided to explore on his own. He searched for mineral deposits around the Tombstone Hills. As he set off on his own, a soldier told him:

When you’re out there by yourself, you won’t find silver or gold! But instead…

“…you’ll find your Tombstone!”

He remembered that warning when he discovered silver and began mining just South of today’s town of Tombstone. In August 1877 he named his first mining claim “Tombstone.” His next two mines he named Graveyard No. 1 and Graveyard No. 2.2 With a sense of humor – don’t you think?

So they called the town “Tombstone” after his mine.

All Tombstone’s Mining History>

People teemed into town, with tradespeople fulfilling their needs. Mercantiles, restaurants, corrals (yes: the O.K. Corral!), and saloons.

Silver mining drew people since early 1880. With only about 400 mining jobs available, not all found work. Others came for ill-gotten gains. Silver nuggets in mine areas, supply wagons, and stage-coaches were targets. Eventually Cochise County cowboys began getting the stagecoach hold-up reputation.

Some entrepreneurs supplied surrounding Tombstone Territory ranching outfits. These cattlemen – ranch workers – the typically thought of cowboy – entered Tombstone. There to buy feed, sell cattle, deposit funds, and do other tasks. Often staying overnight, having a meal, sometimes visiting the Red Light District.

Common entertainment was a Wagering Game: Faro, Poker, etc. Mostly in a saloon. Many of these Cochise County cowboy types came armed with guns and/or knives. Then alcohol entered the mix. Often the combination led to violence. Some Cow-boy personalities roaming the area of Cochise County were definitely up for that!

What Does It Mean to be Called A Cowboy?

In 1878 the term “cow boy” resembled the person we generally think of today. The Dodge City Times described him as one of the many men who drive the cattle to town, “to herd and care for them.” Even though, they’d sometimes get in trouble, ending up in jail for the night.26

Cochise County Cowboys

Connected To Tombstone’s

Historical Problem With Violence

The Chiricahua Apache Reservation was set up in Southeastern Arizona, abolished in 1877. Cattlemen started grazing cattle there. Their herds attracted rustlers. Some cattlemen were the rustlers! The term “cow-boys” began to be applied to them.

The newly formed Tombstone City government instituted Ordinance Number 9 on April 12, 1880. To prevent violence, concealed weapons – specifically guns, rifles, and knives – couldn’t be carried into town. At least without a permit. Anyone entering town would need to put up any such weapons.

That ordinance was difficult to enforce, and flaunted by the lawless, particularly those becoming known as Cochise County cowboys. Tombstone’s reputation as a Wild West town had begun. One writer noted “Our town is getting a pretty hard reputation. Men killed every few days, besides numerous pullings and firings of pistols and fist fights.”1

Who Were Cowboys in Tombstone?

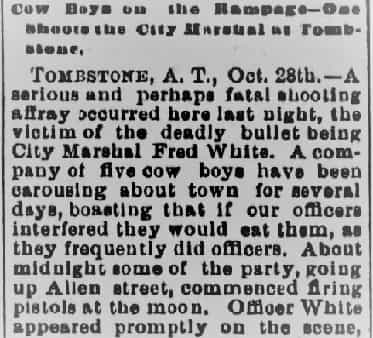

One incident really set people on edge against the “Cow Boys” happened in October 1880. Curly Bill Brocius was drinking hard at Thomas Corrigan’s saloon. With him were stockmen Frank Patterson, Ed Collins and Dick Lloyd, plus three local miners.2 After midnight they were out on Allen Street shooting pistols into the air (never a good idea!). Marshal Fred White came up, requesting their weapons, while grabbing Curly Bill’s gun-barrel.

Wyatt Earp ran up, too. The gun went off and White was shot in the gut. Wyatt took his gun and slammed Bill in the head. Marshal White died hours later.

This was portrayed in the 1993 Tombstone Movie – if not quite accurately! For instance, were these Cowboys really identified by their red sashes?? Sorry, if we disappoint – but no. Read on for more on these real Cochise County Cowboys!

In March 1881 another episode outraged locals.

A Stagecoach robbery: the driver and one passenger killed. Cochise County Cowboys immediately were suspect. A posse gathered to track the culprits, heading out right away. Among them: Pima County Sheriff Bob Paul, Wells Fargo’s Marshal Williams, “Deputy U.S. Marshal V. W. Earp and his two brothers [and] Sheriff John H. Behan, of Cochise County…”3

The Cochise County Cowboys attracted attention through-out the country. Three Cow Boys robbed the safe in Springer & Hacke’s store in Charleston. Deputy Sheriff Belle’s posse tracked them and shot two: Burns and Clubfoot Jack. Nashville reported this story April 22, 1881 on their front page.4

The Fort Wayne Gazette reported a gang of cowboys killed the Hazlett brothers (murderers themselves!). Twenty surprised these brothers when playing cards in a saloon. None ever held to account. Also noted in Pittsburgh and York PA newspapers.5,6,7 Other newspapers carried the story. The sensation of so many Cow Boys attracted much attention toward Cochise County and Arizona!

Leader of the Cochise County Cowboys

And The Tombstone Cowboys

A local incident got further recognition in the East. The problem began with cattle ranches near the former Chiricahua Reservation, the Sulfur Springs Valley. Cattle thieves worked both sides of the International Border. Cochise County Cow-Boys were known, or alleged to be involved. Some names you’ll recognize working there were Johnny Ringo, Curly Bill Brocius, the Clantons, Frank and Tom McLaury.8

With all these names you’ve heard: some in film, or books you’ve read. Who was the leader of the Cochise County Cowboys? Or was there a leader of the Tombstone Cowboys? Since those “Cow Boys” in Southern Arizona weren’t a formal organization, there was no official leader. Some may feel it was Old Man Clanton. Some think Johnny Ringo took the lead. Many of the cowboys of Cochise County came and went. It’s up for questioning!

Mexican ranchers chased some rustlers in late May 1881, battling and killing three before these Cowboys got back into Cochise County, Arizona. The Cow Boys planned revenge for their friends’ killings. After that seven cowboys, including Old Man Clanton, were near the Border at Guadalupe Canyon, NM. They were driving cattle to Tombstone when attacked by Mexicans in the early morning. The cowboys, including Clanton, were killed, but two escaped.9

Much to-do about the incident spread around, with two Cow Boy eye-witness accounts. It promoted people’s fears. Yet there’s a credible theory that it wasn’t a Mexican retaliation for cattle theft, but an Earp Posse attack. Crawley Dake, Arizona Territory’s U.S. Marshal, had reason to limit the actions of these Cochise County cowboys. Dake was motivated to prevent international animus. Historical telegrams from Dake help to back up this theory.8

Many reports about border incidents were reported in newspapers around the country during August 1881. Versions of the Guadalupe Canyon attack were reported. All in all making for public alarm. Plus concern by governments on both sides of the border.

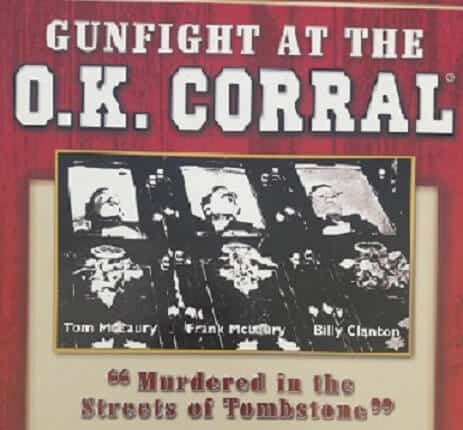

All these circumstances were part of what led to the Famous Gunfight in Tombstone. In a vacant lot adjacent to the O.K. Corral. Between some Cochise County cowboys, the Earps and Doc Holliday.

This shootout was mentioned in newspapers throughout the country. Yet it wasn’t too much of a specific sensation then – just another part of the Cochise County cowboy problem.

A bigger focus began when the town needed to improve its economy. Or it may die! Become a “ghost-town!” Television and movie industries helped. They based shows and films on this Infamous Shootout.

The aftermath of that gunfight brought further Cochise County Cowboy repercussions. Especially via Ike Clanton. He drummed up support for revenge against the Earps and Holliday. This led to more killings, including Morgan Earp. Tombstone politics and continued legal consequences divided people. Eventually the Earps and Doc left Arizona, and the remaining Clantons moved away from Cochise County.

But Cowboy activities were still problematic in Cochise County. Brought to light by an Epitaph article entitled Cowboys and Their Sympathizers. First it quotes Acting Governor Gosper “The people of Tombstone and Cochise County…, have grossly neglected self-government until the lazy and lawless element of society have undertaken to prey upon the more industrial and honorable classes…”10

The governor estimated the number of Cochise County cowboys at “twenty-five to fifty” which he termed as “skilled cattle thieves and highway robbers.” He said bands of Cowboys roamed territory-wide, inferring Arizona and New Mexico. He added others, under a law-abiding pretense, cooperated with the Cowboys for profit.10

The Acting Governor sent a letter to Washington. President Arthur brought it to the attention of Congress. His recommendation was they amend the Posse Comitatus Act. To allow the military to aid local Territorial authorities to establish law and order.11

A bill was prepared.12 Many in Cochise County, and even Arizona, didn’t feel these Cowboys needed oversight or control! The Congress didn’t go further with it.27

An Epitaph‘s May 13, 1882 published letter related to this Dispatch. From a Charleston resident calling themselves “Argonaut.” It regretted the President’s proclamation.

It said “howling about the cowboy and preaching up a state of terrorism here we all believe to be false and useless.” Also those who harshly derided cattlemen, who they’ve known, didn’t realize they were “honorable, high-minded men in business.” Argonaut explained categories of cowboy:

- Respectably, those who work for their living.

- Not deserving much respect, like those in town gambling, living off others’ earnings and worse.13

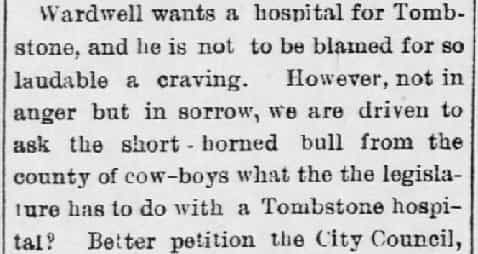

For a while, focus centered on this matter with the legislature. Not on cowboy cattle activities. Cowboys and friends protested the Federal Government’s bothering with Territorial problems.14 By early next year, Cochise County was still known as the “county of cow-boys.”15,16

A February 1883 letter printed by a Tucson newspaper wrote of cross border rustling. “Red Rock” stated horses and mules were stolen from ranches. They tracked them over the Sonoran border. Then cattle were taken from Mexico across the border into Charleston and Tombstone. Found with “American cowboys.”17

Next month the Tucson Citizen commended the New Mexican Governor’s handling their cowboy problem. Saying if we’d had his actions “during the cow-boy days in Arizona, we would have been much better off.”18

The rest of 1883, reports of robbery, horse and cattle smuggling still occurred in Southern Arizona. Expanding more into Graham County. Still not as intense as the year before. But the country-wide reputation was still alive. With news headlines like “The Land of Murder” and “More of the Diversions of the Hell-Hounds of Arizona.” Tucson newspapers started complaining! Tucson’s Citizen wrote “The cowboy element is dwindling down to small numbers and in a few months they will be numbered among the things of the past.”19

But complaints on cowboy activities persisted through 1883. Early the next year Tucson news complimented California’s San Francisco Chronicle. Quoting them, they recognized Arizona had ramped up law enforcement. Their Cochise County Cowboys were now law abiding cattlemen. “Arizona authorities are determined to stamp out the lawlessness…. the era of the cowboy has passed…”20 The Arizona Citizen called for the local immigration bureau to publicize this fact.21

By summer of 1884, a Prescott paper even noted cowboy gun violence had diminished.22 A Phoenix news item told of cowboys who stole freight, but then returned to pay for it!23 An engagement announcement in the Epitaph referred to the groom-to-be as “a prominent ex-cowboy.”24

By 1887 cattle crossing from Mexico to the U.S. were required to be inspected.25 Crime, of course, was to some degree an on-going problem. But the cowboy issue was dying down to virtual non-existence.

Cochise County Cowboys Today!

Today visitors can visit town, check out the OK Corral, Vintage Saloons, and other attractions. Take in the gunfights and local Western shows . They love to entertain you by portraying Cochise County Cowboys. Now it’s all in fun and for entertainment.

We hope when people visit, they’ll appreciate some of its authentic history. Tombstone isn’t an amusement park, or a pretend Wild West town. It’s a real city, with history from the 1800s that had these cowboy issues.

Those who live here take pride in the history, and like to portray it. We welcome visitors. So come over and enjoy what the town has to offer!

References

1 Parsons, George W. (1996). A tenderfoot in Tombstone. The private journal of George Whitwell Parsons: The turbulent years, 1880-82, p 72, Westernlore Press, Tucson AZ.

2 Bailey, L.R. (2004). Tombstone, Arizona: “Too tough to die” The rise, fall, and resurrection of a silver camp; 1878 to 1990. Westernlore Press, Tucson, Arizona. A prime general resource for anything without notation.

3 The Record Union (1881, March 19). The stage robbery – Fears of Disaster, p. 4. Sacramento, California.

4 The Tennessean (1881, April 22) Arizona Robbers, p. 1. Nashville TN.

5 Fort Wayne Daily Gazette (1881, June 23). Particulars of a murder, p. 1. Indiana.

6 Pittsburgh Daily Post (1881, June 23). Killed by cow boys, p 1. Pennsylvania.

7 York Daily (1881, June 24). Killed by cow boys, p. 4. Pennsylvania.

8 Traywick, BT (1996). The Clantons of Tombstone. Tombstone AZ: Red Marie’s Bookstore & Los Angeles: We Print It Inc.

9 The Arizona Weekly Star (1881, Aug. 25). Border warfare. Tucson, Arizona.

10 Tombstone Weekly Epitaph (1882, Feb. 13). Cowboys and their sympathizers, p. 5. Arizona.

11 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1882, Feb. 27). Relief for Arizona, p. 2. Tucson, Arizona.

12 Harrisburg Telegraph (1882, May 4). House, p. 1. Pennsylvania.

13 Tombstone Weekly Epitaph (1882, May 13) From Charleston, p. 2. Arizona.

14 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1882, May 14). Telegraph: Special to Citizen, p. 2. Tucson, AZ.

15 Perrysburg Journal (1882, May 19). General news summary: Interesting home and foreign news – Domestic, p. 1. Ohio.

16 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1882, Sept. 10). P. 2. Tucson.

17 Arizona Daily Star (1883, Feb. 18). Harshaw, p. 4. Tucson.

18 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1883, March 4). P. 2. Tucson.

19 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1883, Sept. 29). Coast notes, p. 2. Tucson.

20 The Arizona Sentinel (1883, Dec. 15). P. 2. Yuma.

21 Arizona Weekly Citizen (1884, Feb. 23) P. 1. Tucson.

22 Mohave County Miner (1884, June 15) P. 1. Mineral Park, Arizona.

23 Weekly Republican (1884, July 31). From Saturday’s daily, p. 4. Phoenix, Arizona.

24 Daily Gazette (1885, Feb. 9). A dismal town for a honeymoon, p. 2. Fort Wayne Indiana.

25 Tombstone Daily Epitaph (1887, March 5). Inspector’s notice, p. 4. Arizona.

26 Gazette, Sterling (1878, June 22). Doings at Dodge, p. 4. Correspondent (Rice Co.), Dodge City Times. Kansas.

27 Name Redacted (2018, Nov. 6). The Posse Comitatus Act and related matters: The use of the military to execute civilian law. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved from everycrsreport.com/files/20181106_R42659_a9b336fa9e37e2302a210433da31f27bd3287cdd.pdf

Newspaper clippings thanks to our subscription at https://www.newspapers.com/